Block contracts have been widely used throughout the UK, and continue to be the main payment system for hospitals in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In England, the national tariff (payment by results) currently dominates payments made to the acute sector.

New, integrated models of care mean that other ways to pay providers may become more dominant.

Block contracts

A block contract is a payment made to a provider to deliver a specific, usually broadly-defined, service. For example, a hospital could be given a block contract to undertake acute care in a particular area.

How the value of a block contract is calculated varies widely. It can be set through a measure of patient need or it may be based on the historical spend of a particular service.

Pros

- They are timely, predictable and relatively flexible.

- Payments are made on a regular, usually annual, basis.

- Some commissioners and providers favour block contracts because of the low transaction costs.

- Often used where other payment methods would not be financially viable because of low activity levels or budgetary constraints.

Cons

- Lack of transparency and accountability after a payment has been made to a provider.

- As block contracts are made in advance of a service being delivered, unexpected pressures such as increased patient demand or cost of care are not taken into account.

- They do not incentivise improved clinical care or efficiency.

Capitation

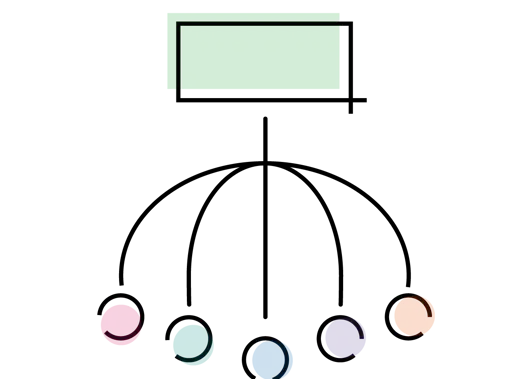

Capitation is a payment system where lump-sum payments are made to care providers based on the number of patients in a target population, to provide some or all of their care needs. The capitation payment is not linked to how much care is provided.

Capitation is used to determine core funding for UK general practice. However, most sustainability and transformation plans in England also aim to move towards an outcome-based capitated budget.

Pros

- As a capitated payment is not linked to how much care is provided, providers have the flexibility to spend money on services they think will secure the best outcome for the patient.

- The potential for more integrated care and evidence that professionals work more closely together when working under a capitated budget.

- Evaluations of programmes elsewhere show they are more cost-effective than other payment systems.

Cons

- Providers are paid regardless of what they deliver - enabling them to provide as little care as possible to minimise costs.

- They do not necessarily take in to account changes in levels of demand, as has been seen in general practice.

- Services delivered by different organisations require significant capabilities on the provider side - eg coordination between primary and secondary care and sophisticated IT to track individual patients' activities.

The national tariff

The national tariff currently dominates payments made to the acute sector in England. HRGs (health resource groups) are used to determine the pricing for health care services.

The national tariff currently dominates payments made to the acute sector in England. HRGs are used to determine the pricing for health care services.

DRGs/HRGs are not used in the NHS in Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales, where block contracts remain the dominant payment system.

Pros

- As providers are paid according to levels of activity, it encourages them to treat more patients, which can lead to reduced waiting times.

- Increased efficiency and system-wide cost containment - HRG-based payment systems are calculated using average costs and so this encourages those hospitals with above average costs to become more efficient.

Cons

- Potential for providers to skimp on quality in order to reduce their costs and maximise profit.

- ‘Cream skimming’ where providers seek out healthier and/or lower-risk patients, or focus on certain conditions or procedures.

- Despite the inclusion of some best practice tariffs and the CQUIN (commissioning for quality and innovation’ framework), the connection between the national tariff and patient outcomes remains poor.

- It does not facilitate a more coordinated approach to health care delivery, across other sectors or parts of the NHS.

Payment for performance

Payment-for-performance schemes refer to payment arrangements where providers are financially rewarded for achieving high performance or quality. Each scheme rewards providers in a unique way.

In primary care, the QOF (quality and outcomes framework) rewards GP practices for achieving performance indicators.

Scotland is considering new payment arrangements to QOF for GP practices and Wales has agreed reforms going forward.

Quality metrics or indicators can be broken down into three categories:

- patient outcomes (such as mortality and readmission rates)

- process measures (such as waiting times and screening rates)

- clinical process measures (such as measuring blood pressure).

Pros

- There is evidence that payment-for-performance schemes can lead to a clinically-significant reduction in mortality rates.

- Can lead to improvements in quality in terms of process and clinical process measures.

Cons

- They are not guaranteed to improve patient outcomes and other quality measures.

- When financial incentives are used to influence performance, leading to a so-called ‘tick box’ culture, those rewards can undermine performance and worsen motivation.

- Can divert attention from other, unrewarded activities.

- Unlikely that they will save money overall.

The BMA's view

The BMA does not support the national tariff, payment by results, as the main way for paying acute providers in England.

Instead we would prefer to see a new payment model introduced that encourages closer working between different parts of the health service, around the needs of patients.

Current payment reforms that focus on capitation look, at present, to be the most realistic way of achieving these aims.