The BMA has produced a new member briefing on the UK Government’s response to the Hewitt Review and the Health and Social Care Committee inquiry into ICSs. The Government’s response provides a strong indication of their plans for ICSs in the near future, so is an important contribution to the ongoing discussion surrounding integrated care.

The BMA submitted evidence to the Health and Social Care Committee inquiry and to the Hewitt Review, informing key aspects of both reports.

We have also produced a separate member briefing on the Hewitt Review, breaking down its key content and recommendations, as well as the BMA’s view on them.

BMA briefing

The Health and Care Act 2022 makes major changes to the NHS in England, including making ICSs formal, statutory bodies with power over NHS commissioning and spending at a local level.

The BMA has produced a member briefing on the Health and Care Act and a dedicated webpage which sets out its the key reforms.

What are ICSs?

ICSs bring together NHS, local authority and third sector bodies to take on responsibility for the resources and health of an area or 'system'. Their aim is to deliver better, more integrated care for patients.

ICSs (integrated care systems) are seen by NHS leaders as the future of health and care integration in England and were central to both the NHS Long Term Plan and Health and Care Act.

As of July 2022, all 42 ICSs across England are operational as statutory bodies as per the Health and Care Act, but they will continue to develop over time.

Under the Act, two bodies will be given statutory status and will collectively make up the ICS or ‘system’:

- ICB (Integrated Care Board): responsible for NHS services, funding, commissioning, and workforce planning across the ICS area

- ICP (Integrated Care Partnership): responsible for ICS-wide strategy and broader issues such as public health, social care, and the wider determinants of health.

ICSs can also choose to use the integrated care provider contract, a more intensive and controversial model of integration. However, only an extremely small number of areas have actively sought to utilise the integrated care provider contract to date.

When changes will come into effect

ICSs are statutory bodies from 1st July 2022, though they have been effectively operating as ICSs for a significant period before this.

The BMA view

The BMA is supportive of efforts to improve collaboration both within the NHS and across the health and care sector, likewise, we recognise the potential value of greater integration.

However, we do not support a single model of integration and have been highly critical of the approach national bodies have taken to the development of ICSs and their predecessors, STPs. The BMA also actively opposed the Health and Care Act during its passage through Parliament and campaigned vociferously for it to be heavily amended.

More specifically, we believe that it is essential for ICSs to

- protect the pay and conditions of all doctors

- ensure strong voice for clinicians throughout ICSs and their substructures

- be free from private involvement, particularly and in any all decision-making bodies

- fully respect and not interfere with existing local and national negotiation processes for pay and conditions.

As reaffirmed at ARM 2022, our call for a strong clinical voice within ICSs encompasses calls for board-level representation for LMCs (Local Medical Committees), LNCs (Local Negotiating Committees), and an independent, properly qualified, and appropriately registered Public Health Consultant.

BMA analysis of new ICB constitutions

The BMA has analysed all 42 ICB constitutions and found a critical lack of both clinical leadership and public health expertise on the boards of the newly statutory bodies.

- none of the 42 ICB constitutions include a role for a representative of hospital doctors, or make any reference to LNCs

- 26 ICBs have the statutory minimum of one primary care representative, only 17 ICBs specify that their primary care representative will be a GP, and only one lists a local LMC as an observer (non-voting) member

- just two ICBs guarantee voting positions for public health specialists, seven ICBs establish that a voting member (from a Local Authority) should have knowledge and experience of public health, and 13 will offer non-voting roles to public health specialists

- disconcertingly, 20 ICB constitutions fail to mention any public health role at all.

These glaring gaps in clinical leadership must be identified and addressed to ensure ICSs have the necessary skills and expertise to carry out their functions.

How ICSs work

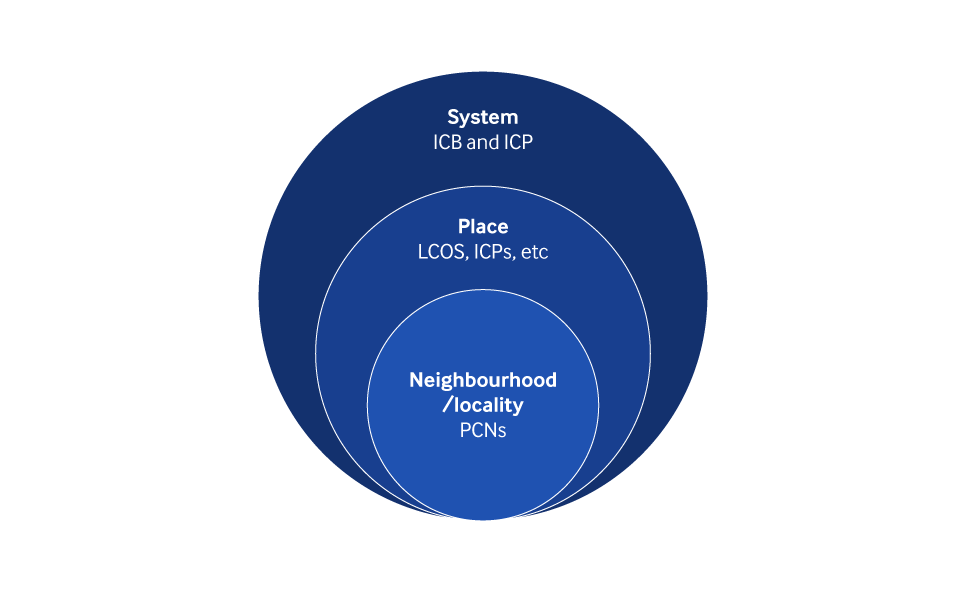

ICSs work on three key levels.

System

ICSs are made up of two core statutory elements at system level, where major decisions are taken, and overarching strategies agreed:

- ICB (Integrated Care Board)

ICBs replace CCGs and are focused on core NHS services, with responsibilities including NHS funding, commissioning, and workforce planning. - ICP (Integrated Care Partnership)

ICPs have a broad focus, covering ICS-wide strategy, public health, social care, and wider issues impacting the health and wellbeing of the local population.

Place

Otherwise referred to as Place-based Partnerships, ‘places’ are normally based around towns, cities, or major NHS trusts within a system. Work at ‘place’ level centres on the planning of localised services and secondary and community care. NHS England sees ‘place’ as the key driver of change within ICSs and they are expected to be where the majority of work actually occurs.

Neighbourhood

Neighbourhoods – or localities in some ICSs – are essentially based around populations of 30,000 to 50,000 people. Multi-disciplinary teams are central to work at this level, with clinicians and health professionals from a wide range of NHS and local authority services working together.

Graphic showing the broad structure of an ICS

Graphic showing the broad structure of an ICS

CCGs and ICSs

The Health and Care Act dissolves CCGs (Clinical Commissioning Groups) and transfers their powers – including over commissioning and funding – to ICBs.

NHS England has stated that most CCG staff will be transferred to, and be employed by, the relevant ICB. However, it is expected that some senior roles, including clinical advisory roles, may be lost in this process.

Implications for doctors

NHS England has stressed that clinical representation will be central to the leadership and progress of ICSs. However, the BMA is concerned that many ICSs lack proper clinical representation at board level.

Under the Act, ICBs are required to have at least one representative of primary care on their board - which in practice is typically a GP. NHS England also requires ICBs to have a medical director at board level, this person may come from any branch of practice and sits alongside a nursing director. There is no guarantee of any further clinical representation on ICBs, which have all determined their wider membership themselves.

LMCs (local medical committees) and LNCs (Local Negotiating Committees) – which represent GPs and secondary doctors respectively – have frequently reported low levels of engagement with their local ICSs. It is critical, therefore, that ICSs reach out to and actively involve their local LMCs and LNCs – including ensuring they have formal roles within their board and decision-making structures. Equally, both LMCs and LNCs should directly lobby their local ICSs to amplify their voices within them.

It is also essential that ICBs and ICPs, as the central functions of an ICS, include an independent, properly qualified, and appropriately registered Public Health Consultant in their decision making structures and boards. Again, this has been lacking in many ICSs to date.

The lack of oversight of and guidance for the development of ICSs prior to the Act has meant that there has been no clear sense of exactly what the model should look like, or what its responsibilities should be. This has limited the accountability of nascent ICSs and has made it difficult for clinicians and the public to see how their health and care system is changing.

The Health and Care Act and the creation of ICSs as statutory bodies should go some way to resolving this. Though NHS England remain clear that ICSs will be allowed to develop with a high degree of freedom and in a permissive environment, meaning that consistency across the 42 may be limited. The CQC is also considering how its model of regulation and inspection needs to adjust to incorporate an effective overview of ICS performance.

There also remains significant concern among GPs that the ICS model will be dominated by NHS trusts. This concern has been heightened by the decision to have CCGs (clinical commissioning groups) absorbed into ICBs. ICSs must, therefore, make sure there is a strong GP voice within their structures and allow for proper local challenge of their plans from all organisations.

However, it is also critical that secondary care representation and voice within ICSs is not limited to trust managers, which cannot reflect the needs and experiences of frontline hospital doctors. Therefore, a strong secondary care clinical voice is essential within ICSs.

More developed ICSs are already pooling resources and taking a system-wide approach to financial management, something set to become more and more established in the near future. Organisations within ICSs also adopt and adhere to a shared ‘control total’, which in effect binds them to meeting a collective target for financial performance.

However, as many trusts already struggle to adhere to their own control totals, placing pressure on ICSs to meet a system-wide total may be an ongoing risk.

Drastic cuts to local authority funding have stretched budgets in both public health and social care. This makes it harder for services to relieve pressure on the NHS and risks undermining integration. NHS England must take this into account when system control totals are set and when priorities for integration are agreed.

The co-ordination of care across wider areas is expected to increasingly involve doctors working across multiple sites and as part of MDTs.

This could give doctors the chance to work in different environments and more closely with colleagues across primary and secondary care, something which has been identified as improving patient care by doctors.

It is possible that organisational mergers may take place as a consequence of ICS plans and local service transformation, with contracts transferred to other trusts via TUPE (transfer of undertakings (protection of employment)).

All doctors should, at the bare minimum, be employed on nationally agreed terms and conditions, with their training time fully protected. Any changes must only happen in

consultation and with the agreement of the BMA.

We are aware that some ICSs are looking to adopt system-wide HR policies, including on critical issues like locum rates. The BMA has opposed these attempts a local level and remains committed to local, place-based negotiations alongside nationally-agreed contracts – ICSs should not and cannot overstep their authority in this sphere.

However, as workforce planning and wider performance management takes shape at ICS level many are considering system-wide decisions that will have an impact on doctors throughout the ICS footprint. Therefore, it is essential that LMCs and LNCs engage with their local ICSs and also work together to gather information and amplify their voices locally.

The BMA has been consistently critical of competition within the NHS, which we believe is bad for patients, staff, and integration.

The ICS model’s focus on collaboration over competition could, then, allow integration to flourish. But to ensure that this can happen, costly and burdensome rules on competition should be removed.

The Government’s Health and Care Act hopes to achieve this by removing Section 75 of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, which forces commissioners to competitively tender for contracts.

However, we remain concerned that the proposed replacement - the Provider Selection Regime - could allow for contracts to be handed out without proper scrutiny. Likewise, we are clear that any new system must prioritise the NHS as the preferred provider of NHS contracts and be fully transparent.

Many ICSs have faced significant challenges in their development and are still some ways behind the frontrunners in their development. This disparity presents the risk that a two-tier system could emerge, with levels of integration varying widely.

The NHS Long Term Plan did include a commitment to provide additional assistance for the least advanced systems, though it remains unclear how effective this has been.

Principles ICSs must meet

We will continue to judge ICSs and their plans against our principles for integration, which we expect them to meet:

- ensure the pay and conditions of all NHS staff are fully protected

- protect the partnership model of general practice and GPs’ independent contractor status

- only be pursued with demonstrable engagement with frontline clinicians and the public, and must allow local stakeholders to challenge plans

- be given proper funding and time to develop, with patient care and the integration of services prioritised ahead of financial imperatives and savings

- be operated by NHS and publicly accountable bodies, free from competition and privatisation.