Engagement within any organisation is important. It allows staff to actively contribute within their normal working role to maintain and enhance the performance of an organisation.

Engagement is particularly important within the NHS as the service adapts to challenges from increasing demand under financial constraints.

Why medical engagement matters

We have called for better and consistent engagement within the NHS for some time.

Better engagement will improve service planning and outcomes for patients, as well as have a positive impact on the morale of the workforce.

Good engagement in practice

Together we can build a stronger culture of engagement within the NHS. There are good examples of medical engagement from across the UK that we can learn from.

Find out more detail from the case study videos below, which showcase these good examples.

Child protection reports

Alan Mitchell is a GP in the west of Scotland. See how medical engagement improved child protection reports for social work services.

Surgical rotas

Sarah Hallett is a paediatric doctor in South London. See how medical engagement addressed a patient safety group's concerns about surgical rotas in secondary care.

BMA SAS charter

Vaishali Parulekar is an associate specialist in radiology in Oxfordshire. See how medical engagement led to the implementation of the BMA's SAS charter in secondary care.

Improved processes

Anthony Dyal is a locum surgical doctor in Londonderry. See how medical engagement led to improved processes in acute care.

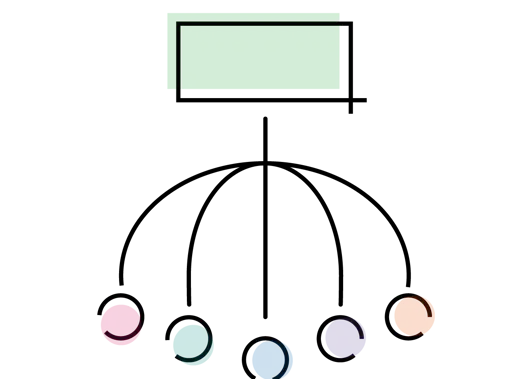

10 principles for medical engagement

Following two member workshops, the BMA has developed 10 principles which form the foundation of what good medical engagement should look like.

Successful engagement encourages input from a wide range of perspectives and experiences.

Everyone working in the NHS should feel empowered to engage and know that their contribution will be taken on board.

For our members, this means all doctors from all backgrounds, all healthcare settings, starting as medical students.

This includes doctors, such as resident doctors and speciality and associate specialist doctors, who often face greater barriers in engaging.

Engaging experts who provide care to patients in how to improve quality and outcomes should be at the heart of how the NHS operates.

Therefore, opportunity should be given to staff to do so in a way that is practical for every job.

Pressures within the NHS are widely acknowledged, but time and resource must be found for engagement in spite of the constraints on all parties involved.

For our members, this means ensuring that they have time and space to engage within their job roles, for example having time to attend relevant meetings included within rotas.

There must be a clear understanding of the expectations for engagement from all those involved, along with regular communication.

For our members, this means clarity around engagement. For example:

- the purpose

- how doctors can assist

- what is in or out of scope

- the timeframes

- the process

- who else is engaging

- how the decision will be communicated.

Engagement must take place before any decision is made. It cannot be a one-off event or tick box exercise, and relies on relationships being developed over time.

Engagement should be early in the process and be continuous. It should be a conversation between all those involved in a workplace.

For our members, this will help to build trust between all participants, develop a team spirit and a collective sense of direction.

It will take place for all decisions whether big or small, such as a large service redesign or changes to a rota, and therefore help establish a culture of consistent engagement.

Engagement should be a two-way, proactive and responsive conversation. This means:

- not coming with fixed outcomes

- recognising that clinicians are an essential part of the process

- holding meaningful discussions that lead to co-productive decisions

- a willingness to delegate tasks to the most appropriate person to generate active involvement.

For our members, this means engagement is a partnership between doctors and others working within that workplace to develop ideas to improve a service.

Engagement should be sought through a range of means, both through formal structures and informal interactions.

Engagement requires mutually agreed approaches, and should be flexible and responsive to the needs of individuals and their workplaces.

For our members, this may mean engagement through formal consultation events:

- with an NHS organisation

- by BMA representatives on their behalf

- through informal conversations

- by social media.

Engagement should be done in a way that people feel comfortable to both challenge and raise new ideas. This means building an ethos of a no blame culture.

For our members, a significant concern is that expressing new ideas or challenging proposals is seen in a negative light and may have wider consequences for them. Removing this limitation will encourage greater engagement.

Discussions should be evidence-based. This means engagement should take account of the ideas and expertise of front-line staff caring directly for patients.

Decisions should be driven by evidence, not by financial pressures without proper consideration of patient safety and quality of care.

Our members have clinical expertise that can help develop evidence-based discussions and decisions.

This expertise sits alongside their wider local knowledge of what works and what obstacles or barriers exist.

Engagement should be part of a learning culture, where outcomes are evaluated and discussed, and where individuals can learn from each other.

For our members, this means ensuring the right training is available to doctors throughout their careers. Engagement should support this learning by providing an opportunity to develop solutions.

Regular monitoring and evaluation of engagement is essential in all NHS workplaces to ensure it is taking place effectively.

This may be done through individual team meetings to encourage engagement in specific projects.