Consultants are the most highly qualified members of the secondary care workforce and will often have worked for over thirty years in their specialty.

Retaining older consultants in the workforce will help with the inevitable workload pressures awaiting the NHS for the foreseeable future.

This guidance sets out in detail some of the key drivers for consultants leaving the workforce, in addition to ways in which employers can support consultants to delay retirement and retain them in the workforce.

There is also information on returning to work post-retirement.

This is a shorter version listing our recommendations. You can find more information by downloading the full guidance.

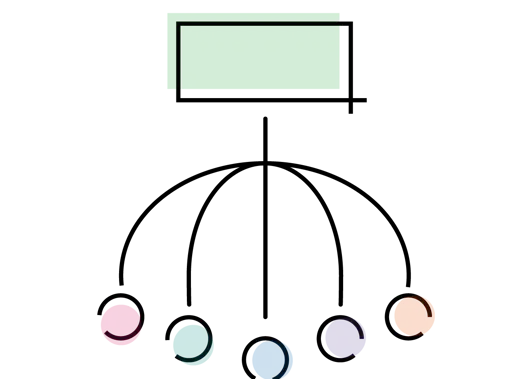

Principles for employers to retain consultants

Retaining consultants in the workforce in the peri-retirement period offers advantage to organisations and to component departments within it.

Organisations are able to increase their clinical capacities, departments are able to deliver more easily their service and training obligations and workloads are shared amongst a greater number of staff.

Employers should accept the principle that retaining consultant medical staff in the workforce is a beneficial thing – employers are unlikely to be able to meet their recruitment requirements without holding on to their existing staff.

Retained employees, moreover, are already completely familiar with the employer’s business processes, there is no lag period for learning or delay while productivity comes up to its maximum value.

Few will consider staying on with an employer if they do not realise that the employer would like them to remain. Employers should let their workforce (in general rather than by individual) know that they would like consultants in the peri-retirement period to stay on.

It is important that both the managerial staff and employees within the organisation all understand the value of retention. This may be important, both to ensure that the opportunity to retain staff is harnessed throughout the organisation and also to ensure that other staff do not feel that they are being overlooked if they do not fall into a 'retention' group.

In addition, it should be acknowledged that there will be a continuing requirement for increased numbers of consultant staff into the future: organisations should be clear that retention policies will be available for younger consultants when they reach an appropriate stage in their careers.

It is essential that younger consultants feel helped rather than impacted by the retention of older consultants: failure to adequately address this issue will undermine support within departments for retention policies.

Consultants at an earlier stage in their career should not expected to shoulder the additional on-call burden, for instance, when this is relinquished by their consultant colleagues nearing retirement. On call frequencies or the frequency of other out of hours work must not rise as a consequence of retention of older consultants.

Departments must either continue their recruitment of new consultant staff to maintain the present frequency or, where new recruitment is not possible, those on calls gaps must be offered as locum slots.

A range of potential offers is likely to have a greater success rate than a single response. Individual flexibility will help too.

The employer’s objective should be to try to encourage staff to remain with the organisation: positive persuasion is needed rather than trying to impose barriers to leaving.

Organisations need to recognise that they are trying to persuade, there is little point in making an offer that is seen as a penalty, for example by offering someone more flexibility during the day but requiring them to take up more night shifts as a result.

While it is important to ensure that the organisation gains some value from these arrangements it must be borne in mind that carrot is likely to more effective than stick in encouraging employees to stay on.

Equally, organisations should not make the process difficult to accomplish, staff may well decide it has become too burdensome.

Different employees or groups of employees may prefer different things. It is important that employers make a retention offer that is seen as desirable, useful and appropriate by the group that is targeted for retention. If the offer is seen as not embodying those features it will not encourage uptake.

Individual local deals will give the retention process a poor local reputation; it may be regarded as biased. Employers should embrace a policy of staff retention that applies to all.

To have a process that becomes discredited will damage its standing in the eyes of the workforce an employer is trying to retain.

Moreover, it should also be recognised that by having a visible and clearly expressed policy it will likely make the trust a more attractive employer for consultants compared to other trusts who lack such a policy.

A clear trust-wide offer establishes in the minds of all consultants that they will be able to access such a policy when they reach an appropriate stage of their career. It must be seen as applicable to all in order to achieve staff buy-in.

All NHS employers in almost all specialty areas are likely to be affected by the need to retain consultant medical staff to a greater or lesser extent.

If nearby employers are quick to adopt attractive retention policies that may be something that attracts staff to want to work for them.

Staff may consider other employment offers - from other employers – if those employers are seen as enlightened, by offering attractive employment conditions not offered by their current employer.

Staff need to be retained, they are unlikely to be retained by an offer that does not offer them what they want or enough of what they want, or is so couched with conditions that it is seen as lacking clarity.

The object of retention policies is to persuade consultant medical staff content to stay with their employer; employers need to ensure policies that are designed to help retention are actually seen by consultants as a useful encouragement to remain.

A rubicon is crossed once staff begin their planning to leave; it may be helpful to try to prevent that mental first step from being taken. Once an employee begins to consider or make preparations to leave then the opportunity to retain them may already have been lost.

Moreover, consultants report that many employers will not confirm the opportunity to retire and return until the consultant has actually formally committed to retirement.

This uncertainty may mean that some consultants delay retirement – and presumably continue to work in circumstances where they now feel less comfortable to work – while others are lost to retirement without returning at all. Retire and return offers should be clear before the point of actual retirement.

Treat all staff fairly, whilst paying attention to their specific circumstances where appropriate. It is crucial that these principles apply to all staff regardless of background, and that all staff feel that they are a valued part of the consultant workforce.

Treating all staff fairly must also mean that younger consultants do not feel penalised as a consequence of an organisations efforts to retain older staff. Younger consultants should, under no circumstances, have to accept a greater frequency of OOH work or on call duties.

Organisations should strive to recruit new consultants so as to maintain on call/OOH rota frequency alongside their efforts to retain older consultants.

There is more than sufficient work, for the foreseeable future, to fully occupy all staff. The acceptability of retention efforts will be undermined amongst younger consultants if they are disadvantaged as a consequence of those efforts.

Acting prior to retirement to encourage consultants to stay

It's likely that keeping consultants in the 'mainstream' workforce will maximise their hours of delivered clinical work.

If an employer’s ambition is to deliver the greatest number of working hours, this seems likely to be a successful strategy.

Steps employers might take to encourage consultants not to retire are outlined below.

Currently much attention is focused on pension issues, particularly those related to or precipitated by pension taxation.

Many consultants have received huge additional taxation charges as a result of annual allowance breeches secondary to pension growth.

There are sound reasons for offering full employer contributions to employees who are forced to leave the NHS pension scheme, perhaps by very large additional tax charges.

It should be recognised that a large proportion of the likely recipients of additional tax charges will be older consultants. For many of that group of consultants they may be able to choose between staying in employment or retirement.

Even where consultants retire and return to work post-retirement (see below) it is likely that the employer would have been able to access a greater amount of working time from that consultant if they could have been persuaded not to retire.

When consultants are forced to leave the scheme but continue to work they are effectively doing the same work, when compared to a colleague who has been able to remain in the scheme, but for 20.6% less reward – ie a reduction in the total reward package equivalent to the value of the employer pension contribution. This is not reasonable.

Quite apart from this, paying the employer contributions to the employee helps to retain the consultant as a full or part-time employee, by removing the financial disbenefit otherwise incurred by leaving the pension scheme and by avoiding the financial incentive towards retire and return.

Full time consultant staff have the right to request to work part-time but there is presently no contractual right to work part-time. At various times of life all of us may have difficulty balancing working lives alongside other responsibilities.

At such times it may be more practical for consultant staff to become part-time workers. Those times may be when consultants have caring responsibilities – that may be childcare but equally may be the care of older relatives – but there will be a range of other circumstances where part-time work would allow consultants to address a range of responsibilities rather than be forced to choose only that with the highest priority.

Going part-time may also be a way of supporting doctors who are managing health conditions or disability to remain an active part of the workforce.

Consultants may occupy their role for thirty years, perhaps even longer. Evidence shows that the prevalence of long-term health conditions and disability increases with age; this needs to be recognised as a possibility when considering career planning.

However, everyone’s individual needs and circumstances can realistically be expected to change somewhat over the course of their working lives, as can their individual capacity to cope with particular demands of a role. This may include the additional pressures of working in urgent and emergency, on-call and night-time working.

Consultants who may need to make changes to their established ways of working may find the prospect of this stressful. Some may be anxious about their ability to fulfil the requirements of their role without certain changes.

If proper support is available to ensure that appropriate adjustments to ways of working can be made, then consultants can often continue to work at, or very close to, their former capacity. But if this support is not available, that stress may encourage consultants to consider retirement instead.

The net result is that instead of retaining a significant proportion of that consultant’s expertise and availability, they are removed from the workforce entirely. It is sensible, therefore, to seek solutions that allow for flexibility in the roles that individual consultants may or may not carry out, including possibly removing night-time and on-call working.

This option may particularly benefit consultants managing ongoing health conditions and may be considered a ‘reasonable’ adjustment in terms of disability equality law, but the benefits of this type of flexibility will also apply to other groups.

It should also be recognised that attempting to continue accommodating work that can no longer be performed comfortably may be detrimental to an individual’s health, increasing the risk of long-term absence, illness or burnout.

There are also potential benefits to assigning particular tasks based on a realistic understanding of individual strengths and capabilities: adjusting the distribution of tasks in this way is likely to increase overall productivity within departments.

Consultants can still contribute to OOH work within their departments, even where this work is no longer on-call work. Many departments run evening and weekend elective clinical sessions; staff might be offered the opportunity to take up some of that work, on a regular basis, in exchange for relinquishing their on-call commitment.

Such a quid pro quo may help demonstrate to colleagues the value of a flexible approach to role distribution, particularly to those consultants who may need similar consideration either now or later in their working lives.

Broadly, these consultants should be valued for what they still contribute, rather than criticised for what they don’t. Gaps should be filled by concurrent recruitment – while recognising that it will be a smaller gap if consultants are retained.

The proportion of NHS doctors who are women has grown every year since 2009 and this trend is expected to continue. Nearly 4 in every 10 (36%) of consultants were women in 2018 compared with only 3 in every 10 (30%) in 2009. Every specialty group has seen an increase in the proportion of women; in some specialities, eg psychiatry, there are now more women than men. Women also make up more than half of all medical students, meaning the proportion of women in the workforce is likely to grow going forward.

The female workforce may face additional challenges around their wellbeing, which employers need to address. A BMA survey of doctors found that over 90% of respondents reported that menopause symptoms impacted their working lives and 38% said these changes were significant. Over 65% reported that menopause impacts both their physical and mental health. Worryingly, almost half (48%) of respondents said they had not sought support and would not feel comfortable discussing their menopausal symptoms with their managers. This failure to support doctors is leading to doctors stepping down from senior positions or leaving medicine earlier than intended.

Focus is needed on effective organisational interventions to support employees going through menopause. Such measures might include allowing doctors experiencing these symptoms to work flexibly and placing an equal focus on supporting employees with the mental, as well as the physical, symptoms of menopause. Line managers and staff undergoing menopause should seek advice from occupational health teams as necessary.

Adjustments to the workplace such as improving room ventilation and easy access to cool drinking water and toilet facilities can make symptoms far more manageable. Attention should also be given to developing cultures where those experiencing symptoms can speak openly and access the support they need. Employers should raise awareness about menopause and provide training for line managers.

Ways should also be explored to bring staff together in an informal setting to share their thoughts, eg through a 'menopause

cafe'.

Employers and managers need to be aware that experiences of menopause vary, for example people who are non-binary, transgender or intersex may also experience menopause. Every individual who is affected by menopausal symptoms should be treated with sensitivity dignity and respect and be able to access support if needed.

Consultants are, by dint of their long training, very experienced. Consultants who are in the peri-retirement stage of their career are vastly experienced, having worked for over thirty years in their specialty area and have likely also worked under a variety of care-delivery methods during that time. Such experience should be recognised and, where possible, used rather than allowed to go to waste; this is particularly relevant in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic and its’ effects.

Mentoring for recently appointed consultant staff has been a useful and welcome development of the past few years. Mentoring has a supportive dimension in respects of its’ advisory and facilitative discussion; it also has the potential for practical support insofar as the mentee can be assisted in the development of aspects of their clinical practice.

Mentors can assist newly appointed consultants in the development of, for example, their practical surgical skills in respect of particular procedures. That might go so far as to formalise the arrangement of a surgeon in the prelude to retirement helping the development and easing the transition of their newly appointed consultant replacement. It need not be such a direct replacement: mentoring applies equally well to helping more broadly to refine the practical techniques and hone the skills of newly appointed consultants.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that this role has a particular value at present. The focus of the NHS in delivering COVID care has seriously disrupted many training programmes: the necessary concentration on urgent COVID care has meant that trainees have been unable to achieve the necessary competencies in many practical procedures.

The difficulty in acquiring those practical skills applies both for trainees and possibly also for recently appointed consultants, who may have preferred to have greater experience in respect of some procedures prior to appointment. This suggests a place where mentoring might be able to assist by providing the opportunity for personalised assistance/supervision of practical procedures by experienced practitioners. Such personalised assistance could apply to recently appointed consultants but could equally assist trainees in the development of their practical skills.

The pandemic suggests potential further roles for long-serving consultants. Many changes to clinical and other practices have been introduced as necessary responses to the COVID outbreak; there is interest in preserving some of these introductions or perhaps continuing to develop them into the future. While it may not be possible to predict the shape of the future exactly it is clear that there is, at present, an appetite for system change within the NHS.

Consultants in the peri-retirement period have long experience of working within the NHS in general and the local NHS in particular: they are a powerful element of local organisational memory and may well have experience of previous iterations of system design. It seems wasteful if local health systems do not take the opportunity to use that experience to help inform and shape current system redesigns.

It should be noted that these mentor /advisor roles, in addition to other educational roles such as educational supervision of trainees, are suitable for consultants in the peri-retirement period, both before actual retirement and after retirement and return to work.

Returning to the workforce after retirement

Many employers offer 'retire and return' arrangements. Consultants retire from their full or part-time roles and return to work post-retirement, usually with a reduction in delivered clinical sessions. Consultants are able to access pension payments and take up paid employment alongside that.

Despite those arrangements being long established there is great variability in how those arrangements are interpreted and applied. Such a lack of clarity regarding the nature of the offer means that some employees do not seek out such an alternative or perhaps are not offered it, their clinical skills and contribution to organisational output are lost as a result.

Employers should have clear and transparent policies regarding retire and return for consultants. Rather than relying on departmental or even individual offers – which make the process look and feel either haphazard or even unfairly applied – employers should agree a local policy that applies consistently across the organisation and is clearly flagged to all employees.

There are several areas where such clarity is needed.

To whom does this apply?

In the case of consultants it is clear that this should be applied to all consultants, across all specialty groups. It should not rely on an individual offer.

What contract is offered?

In all cases this should be the 2003 consultant contract terms and conditions of service. No other local contract should be accepted.

What is the length of the contract?

Many consultants are deterred from seeking retire and return arrangements because they have only been offered a short contract of employment. Such brief and possibly precarious contracts of employment are unattractive and discouraging.

Employers have, in the past, shied away from offering a longer contract period fearing that it would establish enduring employment rights.

This seems to be unnecessary caution; there is little evidence that long term contracts of employment in this context have become problematic for employers.

Moreover, there are examples amongst trusts to offer open-ended contracts for nursing colleagues who have retired and subsequently returned to NHS employment under agenda for change contractual arrangements. It is not acceptable the different standards are applied for consultants in respect of their length of employment contract.

What point on the salary scale is offered?

Most consultants retire at the top of the consultant salary scale. Some employers offer retire and return arrangements that remunerate consultants at other points on the consultant salary scale.

This is not appropriate: employers gain an employee of immense experience - experience of both the clinical specialty and of the local healthcare system – that allows that consultant to function at maximal productivity from the point of engagement.

There is no justification for the offer of remuneration at a lower level; such offers should be rejected. The reduced reward makes the employment offer less attractive – particularly where employers may need to maximise the number of consultants returning to employment after retirement in order to support an inadequate supply of consultant personnel.

Employers should offer consultants their equivalent pay point pre-retirement on return to work.

How much can be earned?

Some employers insist that consultants who have taken up an offer of retirement and return to work may not earn more from their new employment than they earned before retirement. This is not the case.

It is true that there are restrictions on earnings during the first calendar month immediately following retirement. Beyond that there are no restrictions on earnings.

Keeping in mind that organisations want to maximise the delivered hours of work from retire and return consultants it seems illogical to impose restrictions via earnings limits on the number of hours that can be worked.

Pension – pay employer contribution to the employee

There are sound reasons for offering full employer contributions to employees who return to the workforce after retirement.

Consultant returnees to the workforce bring enormous experience and productivity that benefits an organisation’s performance: they should not be discouraged from returning by a reduced total reward package in comparison to their other colleagues.

Pension benefits are part of that total reward package, if returnees are not offered employer pension contributions as part of their package they are, in effect, working for 20.6% less than their other colleagues who remain in the pension schemes.

Moreover, it should be noted that members of the 2015 pension scheme are able to rejoin the scheme after retirement, should they return to work, which will secure the employer pension contributions for those members.

It is not reasonable to offer lesser effective per hour remuneration, by withholding employer pension contributions, to consultant returners who have service in other NHS pension schemes.

Length of service

As noted, returners often have long service within the NHS, before rejoining the NHS for a further period of service. It is inappropriate to require that they complete a further period of service before they can access previously held entitlements such as annual leave or the ability to apply for new style LCEAs (local clinical excellence awards).

Annual leave

Consultant returners have, as noted, long service in the NHS. The 2003 TCS specifies that consultants are allowed six weeks plus two days of annual leave per year, exclusive of public holidays and extra statutory days - the additional two days of annual leave per year are awarded after seven years’ service as a consultant; service duration is specified but not continuous service.

The terms and conditions of service also recognise that consultants are entitled to two days statutory days leave per year in addition.

These statutory days may, by local agreement, be converted to a period of annual leave. Consultant returners, where they had longer than seven years of service in the consultant grade prior to retirement, should continue to receive six weeks plus two days of annual leave per year plus two statutory days leave per year.

Local CEAs

The benefits of old-style LCEAs are crystallised into pension upon retirement. It is not appropriate that old-style CEAs should be retained after retirement. However, new-style LCEAs can be applied for by retire and return consultants. This is the case whether they have been offered a permanent contract, or a fixed term contract.

Our interpretation of schedule 30 is that a further period of a year of renewed employment is not required before such a consultant becomes eligible to apply for and for receipt of new-style LCEAs (or successor).

Consultants who retire and return should have amply fulfilled the schedule 30 TCS requirement for at least one year of service at consultant level. Note: schedule 30 does not specify one year of continuous service nor one year of service in the current post.