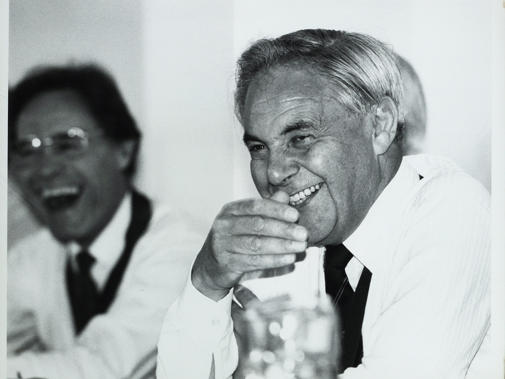

John Marks, who led the profession in a passionate defence of the NHS against the incursion of market forces, has died at the age of 97.

Dr Marks was BMA council chair from 1984 to 1990. In 1989, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government introduced a white paper which said, in Dr Marks’ words, that ‘efficiency in the health service could only come about through competition, in the so-called internal market, an unknown, untried and untested concept in a National Health Service’. It included plans for GP fund-holding and for hospitals to become self-governing trusts.

The BMA responded with a robust advertising campaign which portrayed a complete list of medical bodies supporting the government’s plans (it was blank), a steamroller captioned ‘Mrs Thatcher’s plans for the NHS’, and, most famously, the question: ‘What do you call a man who ignores medical advice? Mr Clarke.’

Ken Clarke, then health secretary, often referred back to the dispute with apparent bitterness in the decades that followed. Some adverts carried a slogan which Dr Marks devised himself: ‘The NHS – under-funded, undermined and under threat.’

Dr Marks later reflected that the poster aimed at Mr Clarke may have been counter-productive as it was a personal attack, but 2,000 doctors joined or rejoined the BMA during the period, a majority of the public polled believed the plans would lead to NHS privatisation, and the pressure may have helped the BMA win important concessions.

Abortion rights

Born in 1925, Dr Marks was the son of a poulterer turned publican. Despite being rejected by two London medical schools – one, he claimed, because he was not good enough at rugby and the other because he was Jewish – he was accepted at Edinburgh University.

He qualified on 5 July, 1948, the day the NHS began. In his early years as a doctor, he served in the Army in the Middle East, and in 1951 a child patient coughed in his face, leading to herpetic corneal ulceration and ultimately blindness in his left eye. He later became a GP in Hertfordshire.

Dr Marks campaigned to protect the rights granted through the Abortion Act. He was strongly influenced by a despairing patient, Betty, who had, in 1968, attempted an abortion at home, having no prospect of gaining one legally.

In his autobiography, The NHS: Beginning, Middle and End?, published in 2008, he wrote: ‘I can still see that young woman lying dead on the bathroom floor with the syringe in her hand and her clothes raised up around her waist.’

She left behind three young children. This was just months before the Act came into effect. Dr Marks rallied support at BMA annual representative meetings when there were parliamentary challenges to the Act, even though it exposed him at times to personal abuse.

I can still see that young woman lying dead on the bathroom floor with the syringe in her hand and her clothes raised up around her waistDr Marks

He is also remembered, during his time as council chair, for leading the BMA’s response to the new challenge of HIV through the publication of a guide, ‘AIDS and You’, in 1987.

The guide won a Plain English Award for its sober and straightforward mix of words and cartoons about how HIV was spread and how it could be avoided. Again, there were elements of the profession and public which strongly criticised him.

He also saw the BMA through a difficult period in which, at the 1987 ARM, the BMA representative body supported HIV-testing without, necessarily, the consent of the patient, a proposal with which Dr Marks strongly disagreed.

BMA council did not implement the resolution, and at the following ARM, representatives voted to change the position to one where doctors needed specific patient consent, with those believing they had grounds to depart from the rule needing to be willing to justify their decision before the courts and the GMC. He reflected in his autobiography that the BMA ‘temporarily took leave of its senses’.

Beating bigotry

CHISHOLM: Marks a 'giant of medical politics'

CHISHOLM: Marks a 'giant of medical politics'

Dr Marks is remembered for his wit and fearlessness. When the Prince of Wales was BMA president in 1982, he caused consternation at a dinner by quoting a letter which accused the BMA of being ‘bigoted’. Dr Marks quickly responded by saying a bigoted organisation would never have elected a ‘Cockney Jewish grammar-school boy’ to its highest political office.

In his retirement, he was not heavily involved in medical politics, focusing on such interests as his stamp collection, a hobby he took up in the 1960s to help him quit smoking; a patient suggested that he spend his cigarette money on stamps instead.

He had hoped Labour would be the saviour of the NHS in 1997, and held his silence as the administration persisted with Conservative measures such as the private finance initiative, until a media interview in 2007 reflected his profound disappointment at the continued involvement of the private sector in the NHS.

When asked for his greatest achievement, he always gave the same answer – marrying his wife Shirley Nathan in 1954. She also became a GP at his practice, and survives him, along with his three children.

After he stepped down as chair he always sat next to me in council in the eyeline of the next chairDr Everington

BANFIELD: He made a real difference to the lives of doctors and patients

BANFIELD: He made a real difference to the lives of doctors and patients

BMA council chair Phil Banfield said: ‘John was an inspirational figure and exceptional advocate and campaigner who made a real difference to the lives and rights of doctors and patients.’

He described Dr Marks as ‘much loved and respected’, and that he ‘could only aspire’ to fulfil the example his predecessor as council chair had set.

John Chisholm, the former chair of the BMA’s GPs and ethics committees, described Dr Marks as a ‘giant of medical politics’. He said: ‘John’s leadership of the BMA campaign against the Thatcher-Clarke NHS reforms, which proposed the establishment of an NHS internal market, self-governing hospitals and GP fund-holding, was masterly and principled.’ He said the campaign influenced public and political opinion and won concessions.

Dr Chisholm said Dr Marks was ‘on the right side of debates about AIDS, HIV infection and abortion’. He added that the practice Dr Marks had in Hertfordshire with his wife Shirley was ‘innovative, progressive and involved in medical education’. (Read his personal tribute below, 'His legacy lives on')

EVERINGTON: Dr Marks displayed a passion for patient care

EVERINGTON: Dr Marks displayed a passion for patient care

Sir Sam Everington, a former deputy council chair, said: ‘In 1989 when I was a junior doctor leading the national campaign to reduce junior doctors’ hours, one of the things we did was land a writ on University College Hospital for making its doctors work unsafe and dangerous hours.

It was done in the name of a friend Dr Chris Johnstone, who worked there. I paid the £80 for the High Court writ, but after a few weeks our costs had increased to £4,000. John took very little persuading to take over the case. Normally the BMA will not take over responsibility for cases started by others.

BUCKMAN: 'John Marks' boy'

BUCKMAN: 'John Marks' boy'

‘Eventually we won in the House of Lords and persuaded Virginia Bottomley, the secretary of state, to give us a new deal. I have been on BMA council for 32 years and John was an outstanding chair with a clear value set based on a passion for patient care, the NHS and for doctors.

'After he stepped down as chair he always sat next to me in council in the eyeline of the next chair! He was a great and wise mentor to me and always had a mischievous sense of humour. He never grew old and always understood the pressure on younger doctors. He was one of the few in my life that I list as an inspirational leader.’

The former BMA UK GPs committee chair Laurence Buckman was a GP partner of Dr Marks. He said: ‘I became John Marks’ last trainee in 1983. Our first meeting started with “You’re a failed hospital doctor. Why don’t you go and make the tea?” Things improved greatly after that. He was an excellent teacher and knew how to encourage his trainees to be more enquiring without making them feel bad for their ignorance.

'He broke me of all my bad hospital doctor habits and showed me how to view the family as the key unit. He knew all his patients and their problems, reciting them often when we were visiting patients at home. Underneath his gruff exterior, there was an empathic caring doctor, who spent much of his time increasing his understanding why his patients needed him. He was a very popular GP who was also a shrewd and well-informed clinician.

‘We got on very well and he became my mentor for the next 39 years. He invited me to become one of his partners and I joined his nine-partner practice in Borehamwood. After several happy years working with John, politically and medically, he retired from the practice – a significant loss for his patients and me.

'Later I moved practice, but we continued to meet and talk often as he guided me through running my practice and medical politics – I was called “John Marks’ Boy” almost until I retired [as GPC UK chair] in 2013 – and he came with his wife Shirley to my retirement dinner to see that I was really going to demit office. He was a source of inspiration and advice throughout my professional and political life, as well as a good and close friend. I will miss him.’

John was a plain-speaking, fearless man of principle and convictionDr Nagpaul

Chaand Nagpaul, who in June stepped down after five years as BMA council chair, said: ‘John Marks was BMA council chair when I qualified as a GP in 1989. It was at the time of the infamous government white paper proposing an internal market in the NHS which I felt represented the antithesis of the NHS’s founding principles.

I recall how proud I felt that under his leadership the BMA was defiantly standing up to the government each time I saw the billboard, "What do you call a man who doesn't listen to medical advice? Kenneth Clarke".

NAGPAUL: 'John was inspirational'

NAGPAUL: 'John was inspirational'

‘John was a plain-speaking, fearless man of principle and conviction and inspired me to get involved with the BMA. I also recall requesting the honour of him nominating me to stand for election on to the BMA GPs committee.’

Dr Marks described the NHS as ‘one of the greatest achievements in history’. He was one of the last to have been a doctor at the time of its foundation, and he spent a lifetime defending it.

His legacy lives on

John Marks was one of the best and most effective chairs of BMA council in living memory. He was chair from 1984 to 1990, serving a six-year term, an exception to the usual three to five years which had not previously been granted since the 1940s.

John served at a time when the power of the professions was being deliberately weakened by political pressure from Government, a weakening of influence that has endured. His time as chair was notable for his clear moral purpose in the role.

John’s leadership of the BMA campaign against the Thatcher-Clarke NHS reforms, which proposed the establishment of an NHS internal market, self-governing hospitals and GP fund-holding, was masterly and principled.

He worked very closely with Pamela Taylor, head of the BMA public affairs division, and with the advertising agency Abbott Mead Vickers on communications during that campaign, delivering highly effective public messages through advertisements and public meetings, although it could be argued ad hominem attacks (What do you call a man who ignores medical advice? Mr Clarke was the message on the sides of buses) might have been counter-productive.

Nonetheless, the campaign was so successful in influencing public and political opinion, despite some backlash against the BMA, that the prime minister considered softening the reform proposals and some concessions were made.

I remember John once saying to me that the best chairs of council were those who had been chairs of the representative body rather than branch of practice chairs, not least because they had a broader understanding of the BMA from having attended meetings of the professional committees and all the branches of practice.

He undoubtedly showed signal leadership on ethical and professional issues as well as trade union issues. While his analysis of who made the best chairs of council might be challenged, his conclusion that an effective BMA chair needed to promote both professional and trade union issues was undoubtedly correct.

As well as his work to protect the NHS, including his support for the junior doctors’ hours campaign, John was also on the right side of debates about AIDS, HIV infection and abortion.

John’s leadership was instrumental in the publication by the BMA of a series of influential statements and guidelines about HIV and AIDS, and in the establishment of the BMA Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health (later the Medical Foundation for HIV and Sexual Health).

The debates about AIDS and HIV at the 1987 annual representative meeting were the most dysfunctional, confused, unruly and heated debates I have ever seen at an ARM.

Motions were being debated that opposed the need for consent and supported breaches of confidentiality. John’s support for consent for testing, consent for disclosure of results, and protecting the confidentiality of patients with HIV infection was unequivocal, clear and ethical.

John asked me to appear on BBC News to ameliorate the damage done to the BMA’s reputation caused both by the passing of an ARM resolution saying that consent for testing should not necessarily be required and by the wider debates on AIDS, which had included speeches in support of the breaching of patients’ confidentiality to protect doctors.

Almost all of the senior members of the BMA were involved in a meeting of council after the ARM (to re-elect John Marks as chair after his first three-year term) and, in his absence, John trusted me to try to reassure the public and the media that doctors would continue to behave ethically.

It was very clear to me that the policy not to seek patients’ consent and the threats to breach patients’ confidentiality were ethically indefensible and that the policy would have to be revisited.

On abortion, the BMA had been one of the early medical organisations to recognise that the 1967 Abortion Act was a practical and humane piece of legislation, and to say so explicitly in its policy. John took a leading role in ensuring that repeated Parliamentary attempts to reverse the legislation or limit its scope were defeated.

I first came across John in his role as joint deputy chair of the BMA general medical services committee, the precursor of today’s GPC. John was one of many senior GMSC members who were very encouraging to me early in my BMA career.

He was very kind about the oral evidence I gave to the Review Body in 1979 – the first trainees subcommittee Chair to do so. John and I served as the GMSC representatives on a working party, in the late 1970s and very early 1980s, chaired by Sir Henry Yellowlees, then chief medical officer for England, which was examining medical advisory machinery in the NHS and the revision of the Grey Book. (In those days, wine was served at lunch at meetings chaired by the CMO. How times change!)

John was also relatively unusual at the time for being a general practitioner who had a doctorate – an Edinburgh MD. A summary of his thesis – The Conference of Local Medical Committees and its Executive: A review of sixty years – was published by the General Medical Services Defence Trust, and is still useful in looking at the development of general practice medical politics from the days of Lloyd George’s National Insurance Act 1911 to the foundation of the NHS and beyond.

John and his wife Shirley Nathan were also strong supporters of the Royal College of General Practitioners. Their own practice in Borehamwood was innovative, progressive and involved in medical education. Laurence Buckman, who later became chair of GPC, was a partner in the practice early in his career.